Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Historical overview

Clusters of galaxies are the largest and most recent gravitationally-relaxed structures in the universe. They typically contain hundreds to thousands of galaxies with a total mass of about solar masses (), spread over a region whose size is roughly 10 million light-years (). Galaxy clusters themselves form even greater structures called superclusters, which are gravitationally-attracted, but not relaxed, collections of ten to one hundred clusters and groups of galaxies. The Milky Way itself belongs to the “Local Group” , which is an aggregation of about 40 galaxies, with the Andromeda Galaxy and the Milky Way as the largest members of the group. The Local Group belongs to the “Virgo Supercluster”, with the Virgo cluster at the center. The Virgo cluster is the nearest cluster of galaxies to our own galaxy at a distance of 60 Mly; another famous cluster of galaxies is the Coma cluster, which is called a very regular cluster, because it is nearly spherically symmetric (see figure 1.1).

The tendency of galaxies to form clusters in the sky has long been noticed (for example Messier (1784) had identified already 16 galaxies, which - as we now know - belong to the Virgo cluster, and he noted that they form a group), but the first to study them in detail was Wolf (1906). A great step forward in the systematic study of the properties of clusters was the work of Abell (1958), who compiled the first extensive, statistically complete catalog of so-called rich clusters of galaxies11The richness of a galaxy is a measure that is basically proportional to the number of bright galaxies in a cluster. It was first strictly defined by Abell for his catalog.. This catalog and its successors (e.g. Abell et al. (1989)) are the foundation for much of our modern understanding of clusters.

The cited catalogs of clusters are based on optical identification techniques. However in the early 1970s extended x-ray emission from clusters of galaxies was observed by Gursky et al. (1971); Kellogg et al. (1972), which had been already correctly attributed to thermal bremsstrahlung several years earlier by Felten et al. (1966). This interpretation requires the space between galaxies in clusters to be filled with a very hot () low density () gas. Remarkably, the total mass in this intracluster medium (ICM) is comparable to the total mass of all galaxies in the cluster. Nevertheless this discovery did not solve the so called missing mass problem in clusters, which was first formulated by Zwicky (1933, 1937). Zwicky (1933) was the first to measure the velocity dispersion of galaxies in the Coma cluster, finding , and he correctly concluded from this fact and his estimate of the Coma’s cluster overall radius, that the cluster mass, which he computed using the virial theorem, must be far greater than the observed luminous mass - the first evidence for dark matter in the universe. In his remarkable paper of 1937, Zwicky also proposed gravitational lensing as an alternative technique for measuring the masses of background galaxies. This technique finally became practicable after six more decades (Tyson et al., 1990), and is now a standard technique for measuring cluster mass (Bartelmann, 2003).

Measuring the masses of clusters is not only important for the search of dark matter. Some of the most powerful constraints on current cosmological models come from observations of how the cluster mass function , which gives the number density of clusters with a mass greater than in comoving volume element, evolves with time (Voit, 2005). The reason why the evolution of the cluster mass function is so highly sensitive to cosmology is simply because the matter density of the universe controls the rate at which structure grows. The cluster mass function can be measured using optical surveys. However it is easier to use X-ray surveys, because in the X-ray band, instead of a collection of galaxies, each cluster appears only as a single source (see figure 1.2),

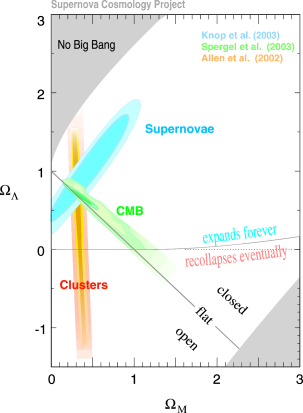

which makes it observationally easier to define consistently cluster properties like the radius. Independently from Supernova IA and cosmic microwave background (CMB) measurements, these and other cluster-related surveys can now restrict several important parameters of the cosmological concordance model (see figure 1.3).

Most of these cluster surveys make use of several relations like the mass-temperature or luminosity-temperature relation, which are only based on observational findings. If gravity alone would determine the thermodynamical properties of the clusters, we would expect clusters to be self-similar, meaning clusters of different size would be scaled versions of each other, leading to a specific simple form of these relations (Kaiser, 1986). However astronomers have known for more than a decade that the intracluster medium cannot be self-similar, because the luminosity-temperature relation of clusters does not agree with self-similar scaling (Voit, 2005). So only by breaking the self-similar scaling of clusters can the observed relations be explained. But it is theoretically still uncertain, which mechanism(s) is (are) responsible for that similarity breaking. Many mechanisms have been proposed including preheating, radiative cooling, feedback from supernovae, feedback from active galactic nuclei (Voit, 2005), shocks, magnetic fields, cosmic rays and turbulence (Dolag et al., 2008). It therefore remains a challenge for the theory of cluster physics to find the responsible mechanisms and explain the relations mentioned above.

1.2 Aim of this work

One of the proposed mechanisms that break gravitationally self-similar scaling properties of clusters is turbulence. Turbulence is also believed to play an important role in explaining the magnetic field strengths of galaxy clusters and the higher than expected temperature of cluster cores (the “cooling flow problem”). However numerical simulations of the influence of turbulence in an astrophysical context in general and especially for clusters have been restricted to measuring passively statistical quantities like velocity dispersion from simulation data (e.g. Dolag et al. (2005)). The active role of small scale velocity fluctuations on the large scale flow could not be treated at all. There are two main reasons for this:

-

1.

Basically turbulence is a physical phenomenon that is far from being understood. The sole currently existing theory is only applicable to isotropic, incompressible turbulence. No accepted theoretical framework for describing turbulent flows in astrophysical environment including compressible, selfgravitating, high Mach number flows exists.

-

2.

Models describing the effective influence of turbulence in fluid dynamic simulations are restricted to a specific length scale. They are not suitable to treat the vast range of different length scales (from cosmological scales down to the thickness of a shock front (, Medvedev et al. (2006)) we need to address when simulating astrophysical environments.

Therefore it is aim of this work to develop, implement, and apply a new numerical scheme for modeling turbulent, multiphase astrophysical flows such as galaxy cluster cores and star forming regions. The method combines the capabilities of adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) and large-eddy simulations (LES) to capture localized features and to represent unresolved turbulence, respectively; it will be referred to as Fluid mEchanics with Adaptively Refined Large-Eddy SimulationS or FEARLESS.

To start explaining the idea behind this ansatz, we first give a brief overview of the theory of turbulence in chapter 2. In chapter 3 we introduce a filter formalism, which is necessary for modeling compressible turbulence according to the ideas of LES. In chapter 4 we use this formalism to derive the filtered equations of fluid dynamics, which are the basis for the introduction of our turbulence or subgrid scale (SGS) model (adapted from work by Schmidt et al. (2006b)) in chapter 5. In this chapter we also analyse in some detail the influence of the turbulence model on the equation of fluid dynamics. In chapter 6 we explain the specific problem of combining LES and AMR in some detail and propose a new method to circumvent this problem. In chapter 7 we comment on several modifications and numerical issues that had to be taken into account when implementing our method into the cosmological fluid code Enzo. We also present the results of several driven turbulence test simulations, showing the consistency of our treatment of turbulence. Chapter 8 summarizes some important facts about cluster physics and we also give a brief introduction to turbulence in cluster simulations. In chapter 9 we describe several issues with our turbulence model when treating turbulence in cluster simulations on cosmological scales. We explain our setup and then describe the main results of a first study of turbulence in galaxy cluster simulations using our FEARLESS approach. Finally in chapter 10 we summarize our findings and draw conclusions about the influence of turbulence in the context of cluster simulations.