Chapter 8 Cluster physics

In the following we want to review some basic theoretical and observational facts of cluster physics. The presentation in this section has been inspired by Pfrommer (2005), Sarazin (1988), Voit (2005) and Plionis et al. (2008).

8.1 Cluster formation

8.1.1 Initial density fluctuations

On very large scales the universe appears homogeneous and isotropic. However the existence of stars, galaxies, and galaxy clusters demonstrates that the universe is not perfectly homogeneous. The early universe must have been slightly clumpy. These perturbations away from the mean density can be characterized as a overdensity field

| (8.1) |

with Fourier transform

| (8.2) |

In case that is isotropic, it can be specified by an isotropic power spectrum

| (8.3) |

If we assume, that the power spectrum has a power-law form , one can show (Peebles and Yu, 1970), that the gravitational potential fluctuations scale as

| (8.4) |

Therefore the magnitude of these fluctuations diverges on either the small scale or the high scale end, except in the case of . This special property makes the most natural power-law spectrum and it also appears to be a good approximation to the true power spectrum of density fluctuations in the early universe.

8.1.2 Hierarchical growth of density fluctuations

Once the universe has been seeded with density perturbations, they begin to grow, because the gravity of the overdense regions attracts matter away from neighboring underdense regions. The gravitational pull of the density perturbations on the smallest scales causes them to collapse first, because, as shown in the last section, the density perturbations have larger amplitude on smaller mass scales. That’s why the standard model of cosmology envisions structure formation as a hierarchical process in which gravity is drawing matter together to form increasingly larger structures. Clusters of galaxies are believed to be the largest structures formed by this process nowadays. Since it is assumed in the standard model that most of the matter in the universe is cold, collisionless dark matter3939The evolution of cold, collisionless dark matter can be described by the Vlasov-Poisson system of equations, see appendix F., the evolution of clusters is basically governed by the collisionless build-up of dark matter from small to successively larger haloes. In the course of this evolution, small structures merge to form larger structures. A full understanding of this hierarchical merging process requires numerical simulations, although its basic concepts can be obtained by means of the analytical spherical collapse model (Gunn and Gott, 1972; Bertschinger, 1985).

However, the accretion process in real clusters is not symmetric. Gravitational forces between merging matter clumps produce a time-varying collective potential which randomizes the velocities of the infalling particles yielding a Maxwellian velocity distribution. This process is known as violent relaxation (Lynden-Bell, 1967) and leads to a state of virial equilibrium. The final outcome of such a virialized, collisionless system would be a self-gravitating isothermal sphere, in which the velocity dispersion is constant and isotropic at every point and the density profile is

| (8.5) |

But this model leads to the unfortunate result of infinite mass and energy for a galaxy cluster, and so it can never exist in nature.

Numerical N-body simulations instead find that the profile of dark matter haloes is described by a universal law (Navarro et al., 1997)

| (8.6) |

where is the central density and a characteristic scale radius. But even with this more sophisticated density profile mass diverges logarithmically with radius. Thus, the cluster’s mass and relations linking that mass to observables depend crucially on the definition of the outer boundary of the cluster. It turns out, that their is no unique definition for the boundary of a cluster, however a common definition, also used in the analysis tools for this work, is the scale radius within which the mean matter density is 200 times the critical density of the universe 4040Although not precisely equivalent, we will call the virial radius and the mass inside this radius the virial mass in our work..

8.2 Intracluster medium

It is widely assumed that the total matter density profile of the galaxy clusters follows the NFW dark matter profile (equation (8.6)), because the dark matter accounts for the biggest part of the total mass. The profile of the baryonic density will also follow the NFW profile on the larger scales, because the baryons follow the gravitational potential of the dark matter. Only in the core, significant deviations from the NFW profile can be expected for the baryonic density, since the baryons are not collisionless and pressure effects should lead to a different profile. This can be tested by measurements of the extended x-ray emissions of the intracluster medium and by numerical fluid dynamical simulations, if the mean free path of the very hot, but dilute ICM is small enough.

8.2.1 Mean free path of the ICM

To determine if the fluid assumption holds for the ICM, it is important to estimate the mean free path. The mean free path of electrons and protons in a plasma is determined by coulomb collisions. The electrons in a Maxwellian plasma undergo Coulomb collisions in a time which is a factor of shorter than the protons. On the other hand, the electrons move faster by the inverse of this factor. Thus, the mean free paths of electrons and protons are essentially equal, with (Plionis et al., 2008)

| (8.7) |

So for typical values of temperature and density of the ICM, we have mean free paths of the order of , which is roughly the scale of a galaxy.

However the ICM contains a significant magnetic field (Plionis et al., 2008), with typical values of , which might be not dynamically relevant on large scales, but it alters the microscopic motions of the electrons and protons. In a magnetic field, charged particles follow helical orbits, gyrating about magnetic field lines. For example the gyroradius of a typical electron is

| (8.8) |

These very small gyroradii probably ensure that the ICM acts as a fluid even when the Coulomb mean free paths are long.

8.2.2 Magnetic fields

The general consensus is that no mechanism can produce significant magnetic fields in the ICM prior to the formation of galaxies and large scale structures (Kulsrud and Zweibel, 2008). So where do the significant magnetic fields in the ICM mentioned in chapter 8.2.1 come from? It is assumed, that weak seed fields were created early in the universe by the so-called Biermann battery mechanism (Biermann and Schlüter, 1951), which predicts fields of a strength . Several theories (e.g. Kulsrud and Anderson (1992)) expect that these seed fields were amplified by Kolmogorov turbulence by a factor of , which yields a magnetic field strength of nowadays, a value which is observationally found in cores of galaxy clusters (Carilli and Taylor, 2002).

But what is the driving mechanism that generates the turbulence amplifying the magnetic field in cluster cores? One process is merger events. Roettiger et al. (1999) found that the field energy after a merger is found to increase by nearly a factor of three (and locally up to a factor of 20) with respect to a non-merging cluster. Since it is quite likely that a galaxy cluster experiences more than one of these events, the amplification will be even larger. Nevertheless the most significant process one can think of is the Kelvin-Helmholtz (KH) instability driven by shear flows, which are common during the formation of cosmic structures. When applied to a cluster core environment, the core dimensions basically define the injection scale and the KH timescale turns out to be , which makes this instability an interesting process to amplify weak magnetic fields (Dolag et al., 2008).

However although numerical simulations could show that the amplification of magnetic fields by shear flows is significant (Dolag et al., 2005; Brüggen et al., 2005), they still have problems explaining the large amplification factors of the initial magnetic fields. Dolag et al. (2005), who used a Magnetic Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamic code, had to assume a initial seed field of at a redshift to achieve realistic magnetic field strengths at . But these problems might be due to the numerical method used. Only recently it has been shown by Agertz et al. (2007), that Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamic (SPH) codes have severe problems describing Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities. Although a solution to these problems has already been proposed by Price (2007), we have to assume, that up to now basically all SPH simulations of turbulence driven by flow instabilities are questionable. Hence a better treatment of turbulence is necessary to be able to study the evolution of magnetic fields in galaxy clusters.

8.2.3 X-ray observations of the ICM

X-ray observations are the most accurate source of information about galaxy clusters today. Observables in the X-ray band include the overall X-ray luminosity of a cluster, emitted by the hot plasma trapped in the cluster’s gravitational potential and the cluster’s temperature inferred from the X-ray spectrum of that plasma. From these data, one can reconstruct density, temperature and entropy profiles. Of course, projection effects, cluster substructure, and deviations from spherical symmetry complicate the generation of these profiles. However only recently Nagai et al. (2007) could demonstrate using data from cosmological simulations, that the methods used by Vikhlinin et al. (2006) for analyzing X-ray data of the the X-ray satellite CHANDRA can reliably recover the distribution of density and temperature of the hot ICM. So given these three-dimensional models for the gas density and temperature profiles, the total gravitational mass within the radius can be estimated from the hydrostatic equilibrium equation in the form4141For a derivation see appendix G.

| (8.9) |

Given , one can then calculate the total matter density profile

| (8.10) |

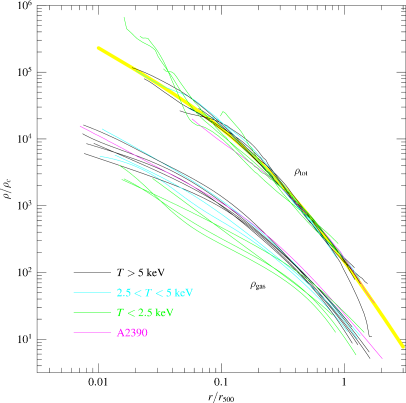

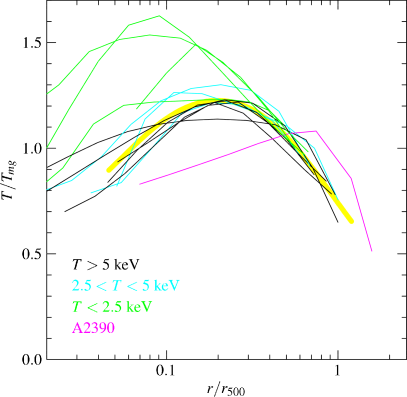

The result of such an analysis (Vikhlinin et al., 2006) can be seen in figure 8.1.

|

|

It is apparent, that the NFW profile provides a good fit for the density profile of the total mass of the clusters. The scatter in the baryonic density profiles is significantely larger and for lower temperature clusters the profiles are flatter towards the center of the cluster. The temperature profiles also show signs of self-similarity, at least for the higher temperature clusters , which are fitted by

| (8.11) |

where according to (Vikhlinin et al., 2006). Also visible from the temperature fit are a isothermal plateau at and the significant decrease of temperature towards the center. This behavior is often explained by assuming some cooling mechanism. Theoretically cooling should lead to lower pressure in the center of the cluster, thereby leading to an even denser core to maintain hydrostatic equilibrium. But, because cooling is even more effective at lower densities, this process is instable leading to catastrophic cooling of the core, which is not observed, giving rise to the so-called “cluster cooling flow problem”. Observationally emissions from the central cluster gas can be detected for gas temperatures between the ambient temperature and , but not below (Peterson et al., 2003), so some sort of heating mechanism seems to be inhibiting the cooling below this temperature. There are plenty of candidates for this - supernovae, outflows from active galactic nuclei, thermal conduction and turbulent mixing - but there is still no consensus on the relative importance of these mechanisms. Turbulence is especially interesting because it was also suggested by Nagai et al. (2007) as mechanism, which might explain some deviations in the computation of the total mass, based on the assumption of hydrostatic equilibrium, without taking turbulent pressure into account.

8.2.4 Turbulence in the ICM

The “bottom-up” model or hierarchical model of cosmological structure formation (eg., Ostriker, 1993) explains the build up of clusters through a sequence of mergers of lower-mass systems (stars galaxies groups clusters). In particular, mergers of galaxies play a fundamental role in determining the structure and dynamics of massive clusters of galaxies. It is found that major mergers induce temperature inhomogeneities and bulk motions with velocities in the intracluster medium (ICM) (Norman and Bryan, 1999). This results in complex hydrodynamic flows where most of the kinetic energy is quickly dissipated to heat by shocks, but some part may in principle also excite long-lasting turbulent gas motions.

In numerical simulations of merging clusters (Schindler and Mueller, 1993; Roettiger et al., 1997; Ricker and Sarazin, 2001; Takizawa, 2005) it has been shown that infalling subclusters generate a laminar bulk flow, but inject turbulent motions via Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities at the interfaces between the bulk flows and the primary cluster gas. Such eddies redistribute the energy of the merger through the cluster volume and decay with time into more and more random and turbulent velocity fields, eventually developing a turbulent cascade with a spectrum of fluctuations expected to be close to a Kolmogorov spectrum (Dolag et al., 2005).

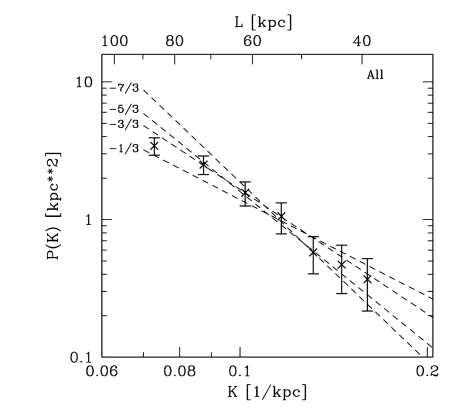

The turbulent nature of the flow could be directly confirmed with the help of high-resolution X-ray spectroscopy of emission line broadening of lines of heavy ions. It has been suggested (Sunyaev et al., 2003), that the X-ray microcalorimeters (XRS) on board of the X-ray satellite ASTRO-E24242Also called Suzaku. should be able to detect this broadening. But due to a critical flaw discovered in the XRS instrument in August 2005, this test has to be postponed until future instruments like XEUS are available. Nevertheless other observations have revealed some signature for turbulence in the ICM. For example Schuecker et al. (2004) analyzed the pressure fluctuation spectrum of the Coma cluster claiming that it scales according to Kolmogorov-Obukhov theory (see figure 8.2).

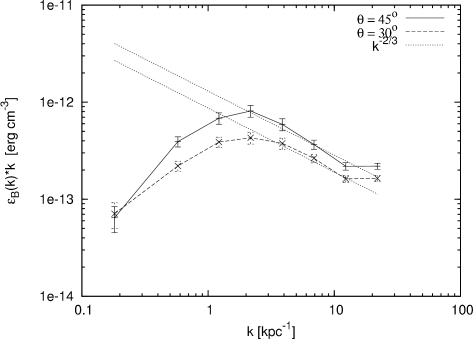

Vogt and Enßlin (2005) makes use of the Faraday rotation effect to investigate the magnetic field structure of the ICM in the Hydra cluster. They extract magnetic field strength power spectra from their data and find a Kolmogorov scaling behavior below a length scale of 1 (see figure 8.3) .

Furthermore the broadening of the iron abundance profile in the core of the Perseus cluster (Rebusco et al., 2005) and other galaxy clusters (Rebusco et al., 2006) and the lack of resonant scattering in the He-like iron K line in the Perseus cluster (Churazov et al., 2004) can also be interpreted as evidence for the turbulent state of the ICM.